21

Volume 1 Issue 7

|

N

ews and

E

vents

When Dr. Crawford became

JCDA

editor

in 1987, the family moved to Ottawa,

and so did the dental collection. The

assortment found a home at the Dentistry

Canada Fund office, where the executive

director had suggested opening a dental

museum. Upon the museum's closure

in Ottawa, the collection moved to the

Museum of Health Care in Kingston in

2010. “When the opportunity came to

house a dental collection, the people

at the Museum were quite interested,

acquiring every piece that was in

storage,” says Dr. Crawford.

The Museum named its new

acquisition the

Crawford

Dental Collection

, to honour

the couple’s impressive

contribution to the history

of dentistry. As the

Museum

explains,

it is

“the most

comprehensive

cross-section

of dental

technology and

practice in

Canada over

the past

200 years.”

It includes dental chairs, sterilizers,

cabinets, anesthesia units, drills, X-ray

units, manufacturer pamphlets, and

much more. Visitors may be surprised to

even find plaster casts of 1957–63 Prime

Minister John Diefenbaker!

“We’re particularly proud of our collection

of ivory dentures,” says Dr. Crawford.

“They’re about 200 years old and

carved out of solid walrus and elephant

tusks. How they were created and how

people wore them is still a mystery.”

Ivory dentures could be one of the first

attempts in cosmetic dentistry. “For the

anterior front teeth, instead of having

ivory, human teeth were embedded

and riveted for cosmetic reasons,”

Dr. Crawford explains.

Probably the most unusual dentures

in the collection are homemade. As

reported by the Kamloops Sentinel in

1968, hunter Francis Wharton of Little

Fort, British Columbia, used deer teeth to

create dentures for himself. For the palate,

he molded plastic wood around the roof

of his mouth, and he fitted the teeth

he previously filled and grinded using

household cement.

Another favourite of Dr. Crawford is a

“finger-powered drill” from 1846 that had

to be turned by hand. “I figured it did

about 75 revolutions per minute.”

With his collection and the

Teeth in Time

exhibition, Dr. Crawford hopes his peers

can acquire the same kind of pride he

feels about being a dentist. “I’m very

proud of the progress of dentistry and

of its contribution to people’s health,”

he says. The collection mirrors the

evolution of our profession. “We were

here. We struggled. We innovated. We’re

only where we are today because past

dentists made amazing contributions to

the profession, with a mind to bringing

optimal oral health to the patients to

whom they were dedicated.”

a

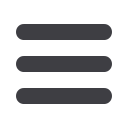

Upper denture from the

early 1800s. The anterior

teeth are human, and

posterior teeth, ivory.

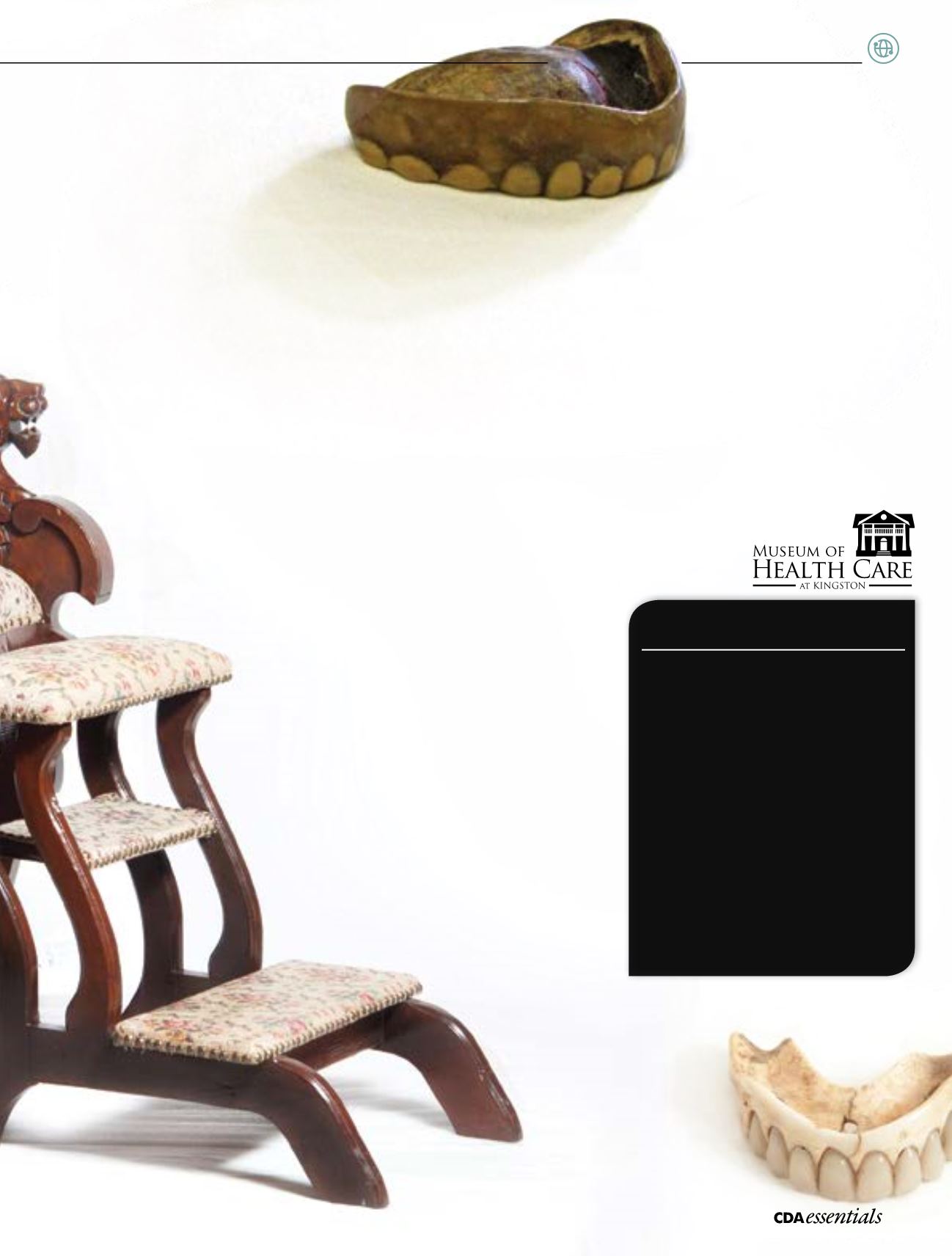

Upper denture created by hunter

Francis Wharton in 1968 using

deer teeth, plastic wood, and

household cement.

Support the museum

To help keep our dental history alive,

the Museum of Health Care needs your

support. Dr. David Tessier is a Kingston

dentist who serves on the Museum’s Board.

He says the Museum always welcomes

potential donations to its collection and

is currently searching for articles from the

mobile dental units used in World War I,

to commemorate the upcoming 100th

anniversary of the Royal Canadian Dental

Corps in May 2015.

Donations can also take the form of

commemorative gifts, endowment funds,

bequests, annuities or recurring contribu-

tions. See

museumofhealthcare.ca/get-involved/donors.html

for details.