Vital Pulp Capping: A Worthwhile

Procedure

• Lawrence W. Stockton, DMD •

Abstract

Despite the progress made in the field of pulp biology, the technique and philosophy of direct vital pulp capping remains a controversial subject. Clinicians are well aware of the immediate and long-term success rates after root canal therapy, but are less certain of the success of vital pulp capping. Researchers have demonstrated that exposed pulps will heal and form reparative dentin. It is realized now that the variable prognosis of vital pulp capping is predominately a restorative issue.

The factors that can produce a successful vital pulp cap are discussed in conjunction with two popular techniques.

MeSH Key Words: acid etching, dental; calcium hydroxide; dental pulp

capping.

© J Can Dent Assoc 1999; 65:328-31

This article has been peer reviewed.

[ Vital Pulp Capping Techniques |Discussion |Conclusion | Reference]

Vital pulp capping is the dressing of an exposed pulp with the aim of

maintaining pulp vitality. Throughout the life of a tooth, vital pulp tissue contributes

to the production of secondary dentin, peritubular dentin (sclerosis) and reparative

dentin in response to biologic and pathologic stimuli. The pulp tissue , with its

circulation extending into the tubular dentin , keeps the dentin moist, which in turn

ensures that the dentin maintains its resilience and toughness. These characteristics

ensure that the teeth can successfully resist the forces of mastication.

Although several studies1-4 have shown that endodontic procedures have an effect on the tooth's dentin, others5 have suggested that it is the cumulative loss of dentin and the loss of the pressoreceptive mechanism6 and not the endodontic procedures that affect clinical performance. Whatever the reason, several studies7-9 have reported the higher failure rate of restored endodontically treated teeth. Since a non-vital tooth requires 2.5 times more of a load than a vital tooth to register a proprioceptive response10-12 the natural protection against an overload is reduced and the probability of fracture increases. Also, because posts do not reinforce teeth7,9,13,14 but may weaken them, restorative procedures that help preserve pulpal vitality and eliminate the need for posts are desirable. However, if endodontic therapy is unavoidable, conservation of the remaining tooth structure is most important.

Major advances in the practice of vital pulp capping have been made, and the emphasis has shifted from the "doomed organ" concept of an exposed pulp to one of hope and recovery. Long-term assessments of vital pulp caps with calcium hydroxide have shown very high success rates.15 Other studies15-18 have demonstrated that the exposed pulp possesses an inherent capacity for healing through cell reorganization and bridge formation when a proper biologic seal is provided and maintained against leakage of oral contaminants. Direct pulp capping should be used only on a vital pulp that has been accidentally injured and shows no other symptoms. Direct pulp capping should not be performed on a pulp that has been exposed as a result of penetrating caries.18 A successful pulp cap has a vital pulp and a dentin bridge within 75 to 90 days.19

The major causes of post-operative inflammation and pulp necrosis are non-sterile procedures and bacterial micro-infiltration of the pulp via dentinal tubules. These may result from contamination of an exposed pulp prior to or during cavity preparation, or as a result of improper sealing of the entire dentin substrate interface when placing the restoration.18,20,21 To decrease the chances of contamination the rubber dam either must be in place from the start of the restorative procedure or be placed once a pulp exposure has been recognized.

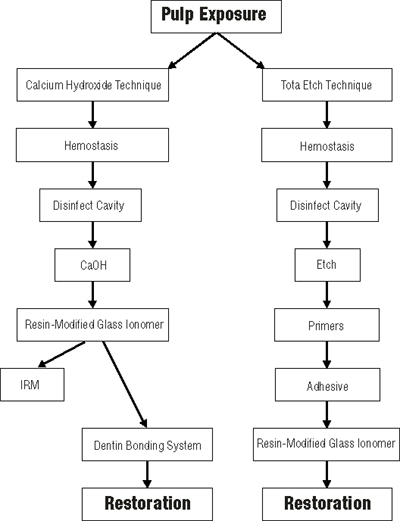

Two techniques have demonstrated success with vital pulp capping , the calcium hydroxide technique15,18 and the total etch technique (Fig. 1).22

|

For vital pulp capping to be successful, the tooth should be asymptomatic or have minimal symptoms and the bleeding must be controlled. This control may be achieved by washing the area with sterile saline and drying it with either paper points or cotton pellets, by using cotton pellets soaked with hydrogen peroxide or 5.25% sodium hypochlorite, or, if necessary, by using a hemostatic agent such as Hemodent15 (Premier Dental Products, Norristown, Pa.). If bleeding fails to stop after two or three attempts, then endodontic therapy should be considered.15,22 Several studies23-28 have indicated that the size of the perforation is less important than obtaining hemostasis.

Following hemostasis, a disinfectant (e.g., Cavity Cleanser, Bisco Dental Products, Itasco, Ill., or Consepsis, Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, Utah) should be placed on the cavity floor.29 The area is then air dried, and calcium hydroxide in a formula such as Dycal (Dentsply Canada Ltd., Woodbridge, Ont.), Life (Kerr Manufacturing, Orange, Calif.) or Ultradent Calcium Hydroxide (Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, Utah) is placed directly in contact with pulp tissue. This step is very important, for the better the contact of the calcium hydroxide dressing with the pulpal wound, the better the healing.15,30 The calcium hydroxide should then be covered with a resin-modified glass ionomer extended onto dentin.31 Subsequently, a permanent restoration can be placed, with a dentin bonding system used to seal the margins of the restoration. An alternative is to place a zinc oxide-eugenol (IRM, L.D. Caulk, Dentsply Ltd., Woodbridge, Ont.) restoration over the calcium hydroxide cap.32,33 Zinc oxide-eugenol provides an excellent seal and, with its anti-microbial properties, makes for a very good temporary restoration. After three months, assuming pulp vitality and no symptoms, the zinc oxide-eugenol can be removed and a more permanent sealed restoration placed.

For the total etch procedure, as with calcium hydroxide, hemostasis must be obtained. The exposure site is then covered with a non-setting calcium hydroxide paste (e.g., Pulpdent, Pulpdent Corp. of America, Brookline, Mass.) and the cavity preparation completed. Following disinfection of the cavity, the enamel and dentin are etched with 32% phosphoric acid for 15 seconds. The acid and calcium hydroxide are rinsed off and the preparation is lightly dried. The entire preparation , including enamel, dentin and pulpal tissue , is treated with a dentin bonding system (a fourth-generation system with a separate primer and adhesive is recommended, as little research has been published to date on the fifth-generation dentin bonding systems). Following placement of several layers of the hydrophilic primer, a thin layer of the adhesive resin is painted onto the enamel, dentin and pulpal tissue and light cured. A second layer of unfilled resin is applied, and a thin layer of resin-modified glass ionomer is also applied over and around the exposure site to mechanically protect the perforation from intrusion of the restorative material during packing or condensation. These layers are also light cured. The restoration is subsequently completed in conventional fashion.34,35

The opponents of calcium hydroxide claim that it does not exclusively stimulate sclerotic dentin formation, dentinogenesis, reparative dentin formation or dentin bridge formation.34 They also claim that it may dissolve after one year, that acids will degrade the interface during etching, and that calcium hydroxide does not adhere to dentin and will not adhere to bonding resin composite systems. One study36 found that calcium hydroxide bases under resin composite restorations tended to pull away from the cavity surface during resin polymerization, leaving a gap between the calcium hydroxide and dentin. Cox and others37 found a high rate of multiple tunnel defects (89%) in dentin bridges under calcium hydroxide. This high rate of defects, they suggest, places the long-term therapeutic effect of calcium hydroxide in serious doubt. They also suggest that calcium hydroxide disintegrates and is lost over a period of time.

It has been suggested that a very small exposure, and certainly a near exposure, cannot be treated with calcium hydroxide, as it is essential that the calcium hydroxide dressing make contact with living pulp tissue.15 In addition, Pashley38 states that there may be little difference between a vital pulp cap and a situation where the remaining dentin thickness is less than 1 mm. He attributes this similarity to the high permeability of the dentin near the pulp. In a recent study,39 opponents of the total etch technique found a 40% loss of pulp vitality over a period of 75 days with three bonding systems on exposed primate pulps. Of the remaining surviving pulps, only 53% even attempted bridge formation. Proponents of this technique point out that germ-free studies40,41 have shown that pulp heals rapidly even when bonding agents are placed directly on pulpal tissue.

The healing of pulp exposures may depend on the capacity of the capping material33 to prevent bacterial microleakage. Pashley42 states that to minimize the pulpal response, restorative materials must seal the cavity margins, prevent microleakage and block bacterial substrates from penetrating through dentinal tubules to the pulp. However, if microleakage around various restorations could be measured in vivo, it is likely that all would exhibit some degree of leakage.38 If these teeth remain asymptomatic, it is probably because the rate at which exogenous materials permeate across dentin to the pulp is balanced with the rate of removal of these materials by pulpal circulation, thus ensuring pulpal vitality.40 Therefore, it is desirable to maximize the barrier effect of dentin to provide the best pulpal protection.38 Each situation must be assessed to determine which method is most likely to achieve a maximal barrier effect.

A dentist's inability to perform proper pulp cap procedures can lead to microbial contamination, leftover dentinal debris in the wound and a lack of a dentin seal. Poor operator performance, therefore, rather than the inadequacies of the medicament, may be the cause of pulp-cap failure.15 In the case of recurrent pulpitis, therefore, one must distinquish between pulp-cap failure and failure of the restoration subsequently placed over the pulp-capping agent.43

Mechanical exposures are more likely than carious exposures to be successfully capped. If the operator properly selects the case, obtains hemostasis, disinfects the exposure and the cavity preparation, and adequately seals the exposure and the cavity preparation, success can be obtained with either the calcium hydroxide technique or the total etch technique. Although both techniques can achieve successful vital pulp caps, the calcium hydroxide technique has demonstrated its success over a longer period of time. Which technique offers the better prognosis awaits the results of many more long-term studies.

For unknown reasons, the pulp-capping agent used, and not the procedure itself, has been the subject of controversy among researchers

Dr. Stockton is an assistant professor in the department of restorative dentistry in the faculty of dentistry, University of Manitoba.

Reprint requests to: Dr. Lawrence W. Stockton, Department of Restorative Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Manitoba, D227-780 Bannatyne Ave., Winnipeg, MB R3E 0W2

The author has no declared financial interest in any company manufacturing the types of products mentioned in this article.

1. HeIfer AR, Melnick S, Schilder H. Determination of the moisture content of vital and pulpless teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1972; 43:661-70.

2. Reeh ES, Messer HH, Douglas WH. Reduction in tooth stiffness as a result of endodontic and restorative procedures. J Endod 1989; 15:512-6.

3. Carter JM, Sorensen SE, Johnson RR, Teitelbaum RL, Levine S. Punch shear testing of extracted vital and endodontically treated teeth. J Biomech 1983; 16:841-8.

4. Rivera E, Yamauchi G, Chandler G et al. Dentin collagen cross-links of root-filled and normal teeth. J Endod 1990; 16:190.

5. Sedgley CM, Messer HH. Are endodontically treated teeth more brittle? J Endod 1992; 18:332-5.

6. Lowenstein NR, Rathkamp R. A study on the pressoreceptive sensibility of the tooth. J Dent Res 1955; 34:287-94.

7. Sorensen JA, Martinoff JT. Intracoronal reinforcement and coronal coverage: a study of endodontically treated teeth. J Prosthet Dent 1984; 51:780-4.

8. Lewis R, Smith BGN. A clinical survey of failed post retained crowns. Br Dent J 1988; 165:95-7.

9. Torbjorner A, Karlsson S, Odman PA. Survival rate and failure characteristics for two post designs. J Prosthet Dent 1995;73:439-44.

10. Stanley HR, Pereira JC, Spiegel EH, Broom C, Schultz M. The detection and prevalence of reactive and physiologic sclerotic dentin, reparative dentin and dead tracts beneath various types of dental lesions according to tooth surface and age. J Oral Pathol 1983; 12:257-89.

11. Stanley HR, Broom CA, Spiegel EH, Schultz MS. Detecting dentinal sclerosis in decalcified sections with the Pollak trichrome connective tissue stain. J Oral Pathol 1980; 9:359-71.

12. Abdel Wahab MHA, Kennedy JG. Accuracy of localization of pulpal pain on cold stimulation. J Dent Res 1985; 64:1155-8.

13. Testori T, Badino M, Castagnola M. Vertical root fractures in endodontically treated teeth: a clincial survey of 36 cases. J Endod 1993; 19:87-91.

14. Hatzikyriakos AH, Reisis GI, Tsingos N. A 3-year postoperative clinical evaluation of posts and cores beneath existing crowns. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 67:454-8.

15. Stanley HR. Pulp capping: conserving the dental pulp , can it be done? Is it worth it? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1989; 68:628-39.

16. Cox CF. Biocompatability of dental materials in the absence of bacterial infection. Oper Dent 1987; 12:146-52.

17. Cox CF. Microleakage related to restorative procedures. Proceedings of the Finnish Dental Society; 1992.

18. Baume U, Holz J. Long term clinical assessment of direct pulp capping. Int Dent J 1981; 31:251-60.

19. Stanley HR, Pameijer CH. Dentistry's friend: calcium hyroxide [editorial]. Oper Dent 1997; 22:1-3.

20. Bergenholtz G, Cox CF, Loersche WJ, Syed SA. Bacterial leakage around dental restorations: its effect on the dental pulp. J Oral Pathol 1982; 11:439-50.

21. Cox CF. Effects of adhesive resins and various dental cements on the pulp. Oper Dent 1992; Suppl. 5:165-76.

22. Cox CF, Hafez AA, Akimoto N, Otsuki M, Suzuki S, Tarim B. Biocompatibility of primer, adhesive and resin composite systems on non-exposed and exposed pulps of non-human primate teeth. Am J Dent 1998; 11:S55-63.

23. Forrester DJ, Wagner ML, Fleming J. Pediatric dental medicine. Philadelphia: Lea and Febinger, 1981; 436:436-72.

24. Berk H. Vital pulp capping. Presented at the International Association of Dental Research meeting; 1978; Washington, DC.

25. Masterton JB. Inherent healing potential of the dental pulp. Br Dent J 1966; 120:430-6.

26. Masterton JB. The healing of wounds of the dental pulp. An investigation of the nature of the scar tissue and the phenomena leading to its formation. Dent Pract Dent Rec 1966; 16:325-9.

27. McComb D. Comparison of physical properties of commercial calcium hydroxide lining cements. JADA 1983; 107:610-3.

28. Torneck CD, Moe H, Howley TP. The effects of calcium hydroxide on porcine pulp fibroblasts in vitro. J Endod 1983; 9:131-6.

29. Gwinnett AJ, Tay F. Early and intermediate time response of the dental pulp to an acid etch technique in vivo. Am J Dent 1998; 10:S35-44.

30. Foreman PC, Barnes IE. Review of calcium hydroxide. Int Endod J 1990; 23:283-97.

31. Pameijer CH. Personal conversation, June 1997.

32. Markowitz K, Moynihan M, Liu M, Kim S. Biological properties of eugenol and zinc oxide-eugenol. A clinically oriented review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992; 73:729-37.

33. Cox CF, Keall CL, Keall HJ, Ostro E, Bergenholtz G. Biocompatability of surface-sealed dentinal materials against exposed pulp. J Prosthet Dent 1987; 57:1-8.

34. Cox CF, Suzuki S. Re-evaluating pulp protection: calcium hydroxide liners vs. cohesive hybridization. JADA 1994; 125:823-31.

35. Heitmann T, Unterbrink G. Direct pulp capping with a dentinal adhesive resin system: a pilot study. Quintessence Int 1995; 26:765-70.

36. Goracci G, Mon G. Scanning electron microsocpic evaluation of resin-dentin and calcium hydroxide-dentin interface with resin composite restorations. Quintessence Int 1996; 27:129-35.

37. Cox CF, Subay RK, Ostro E, Suzuki S, Suzuki SH. Tunnel defects in dentin bridges: their formation following direct pulp capping. Oper Dent 1996; 21:4-11.

38. Pashley DH, Pashley EL. Dentin permeability and restorative dentistry: a status report for the American Journal of Dentistry. Am J Dent 1991; 4:5-9.

39. Pameijer CH, Stanley HR. The disastrous effects of the "total etch" technique in vital pulp capping in primates. Am J Dent 1998; 11:S45-54.

40. Brannstrom M. Communication between the oral cavity and the dental pulp associated with restorative treatment. Oper Dent 1984; 9:57-68.

41. Inoue T, Shimono M. Repair dentinogenesis following transplantation into normal and germ-free animals. Proceedings of the Finnish Dental Society; 1988; (Suppl):183-94.

42. Pashley DH. The effects of acid etching on the pulpodentin complex. Oper Dent 1992; 17:229-42.

43. Stanley HR. Criteria for standardizing and increasing credibility of direct pulp capping studies. Am J Dent 1 998; 11:S17-34.

For more information on vital pulp capping, contact the CDA Resource Centre at 1-800-267-6354 ext. 2223, or at info@cda-adc.ca.